|

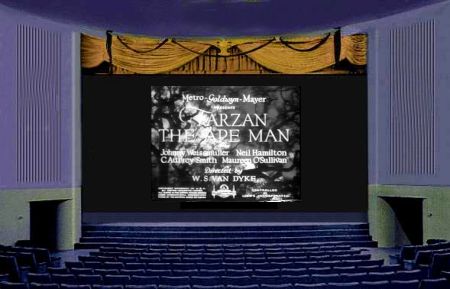

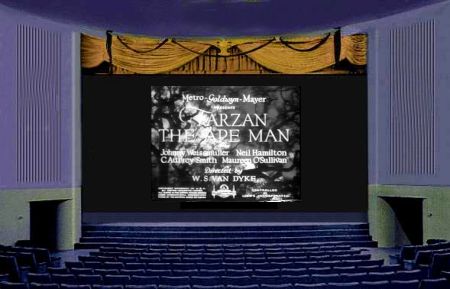

Tarzan Stunt Artists |

Johnny Weissmuller

Bert Nelson, Louis Goebel, |

|

Director |

W. S. Van Dyke |

Running Time: 100 minutes

Production begins: October ,1931

Completed: December 28, 1931

Copyright Date: March 14, 1932

Premiere Date: March 25, 1932

Renewed March 17, 1959

First Showing in Canada: April 15, 1932

Working Title: Tarzan

Tarzan, l'homme singe [Fr]

Tarzan, der Herr des Urwalds [Gr]

Tarzan, l'uomo scimmia [It]

Tarzan, o homem macaco, Tarzan o filho das

selvas [Pg]

Tarzán de los monos [Sp]

Synopsis

The initial entry in the MGM Tarzan films opens at a trading post where two white traders, James Parker and Harry Holt, are preparing to leave on a safari to find the fabled elephants' graveyard. The former's daughter Jane arrives unexpectedly and despite paternal protests insists on accompanying them.

In the face of hostile natives and a forbidding escarpment, the safari reaches the domain of Tarzan, a white man raised by apes. The "white savage" kidnaps Jane, and after a period of adjustment during which fear becomes affection, the girl dutifully returns to her father.

The safari is subsequently captured by savage dwarfs and taken to their village to be sacrificed to a giant gorilla. But Tarzan arrives followed by his elephant friends, who demolish the village while Tarzan rescues the trio of white people.

Unfortunately, Parker has been mortally wounded by the gorilla and wishes only to let a dying elephant guide them to the elephants' graveyard, where he dies and is buried.

Jane decides to remain with Tarzan. Holt will return alone to civilization, but Jane is certain that he will be back with another safari, and the next time, he will need not fear, for Tarzan will be there to help.

Commentary

Studio advertising notwithstanding, Tarzan, the Ape Man was finished rather quickly. Weissmuller was signed October 16, 1931, Maureen O'Sullivan two weeks later, and filming began the day after. The film's initial lensing was completed December 28, some eight weeks after it began, and the first theatrical preview occurred early in February 1932. The cost was listed at $652,675. The profits, based on world-wide returns of five years after its theatrical release, were $919,000.

Hume was assigned scripting duties, and his first draft submitted June 19 picks up where Trader Horn left off. Horn agrees to act as a guide to locate a lost tribe of moon worshippers who live in a ruined city and make regular human sacrifices to a sacred gorilla.

En route, the safari encounters Tarzan, who abducts a member of the party, a woman scientist.

He eventually returns the woman to her group and the party continues its search. When the safari is captured by the ancient tribe and condemned to be sacrificed, Tarzan and his elephants arrive and rescue the group. The woman decides to remain with Tarzan, and Horn and the rest of the safari return to the trading post.

This script makes one think a little of the Opar-Tarzan stories penned by Edgar Rice Burroughs. Perhaps ERB thought so too, or maybe the studio executives did not like the plot, and preferred something a little more contemporary in setting. Whatever the reason, all that remained from Hume's original concept were the episode with the giant gorilla and the elephant stampede. The finished script was submitted in September 1931.

Cast as Weissmuller's rival for

O'Sullivan's affections, Neil Hamilton was a good choice. He was born

September 9, 1899 in Lynn, Massachusetts. Despite a calling , not to

mention his father's wishes, to enter the priesthood, a chance

encounter at a film shoot near his home town changed his mind. From

that moment on, his sole ambition was to become an actor.

At 18, he quit school and went to

Fort Lee, New Jersey, where his natural good looks got him a

modelling job for the prestigious Arrow Collars. In 1920, he posed

for a Norman Rockwell Saturday Evening Post cover , and in 1922 , he

married Elsa Whitmer, with whom he would spend the remainder of his life.

In 1923 he signed a contract with

D. W. Griffith, his first film being The

White Rose, for which he was touted

by film pundits as an up-and-coming star. From 1925 to 1930 he worked

at Paramount before signing with MGM.

1939 was a turning point in

Hamilton's career. First, he was financially ruined by an investment

in the San Francisco World's Fair. Then his acting career plummeted

because of ill-advised comments about important people like Dore

Schary, usually spoken under the influence of alcohol. By 1943 he was

living in a $60 a month apartment, earning $50 a week as a leg man

for an actors' agency.

At about this time and by his own

admission he even contemplated suicide. Then things turned around.

First, he went to work at Universal at $600 a week. Then came Theatre

and Television. In 1948, he became an MC for a TV show called

Hollywood Screen Test.

In the 1960s, he was hired to play

the Commissioner on the camp TV series Batman. And in 1969, he did a

cameo for Norman Rockwell's America calling to mind the cover he had

posed for in 1920.

On September 24, 1984 Hamilton

passed away from complications arising from a severe case of asthma.

Even by today's standards, Tarzan, the Ape Man is a fine adventure film. But to judge it fairly, one has to consider the age in which it was made. Prior to 1932, the Tarzan films were silent, and the histrionics were exaggerated to compensate for the lack of sound. And with the possible exception of Frank Merrill, the physiques of the actors who portrayed Edgar Rice Burroughs' ape man, left much to be desired. Moreover, MGM was the first major studio to attempt a grade A feature film of the jungle lord. Add to that Irving Thalberg's motion picture genius, and the result had to be splendid. Even Edgar Rice Burroughs, who regularly complained about the manner in which his jungle hero was portrayed on screen, was enthusiastic, and in a letter he communicated this enthusiasm to the film's director.

My dear Mr. Van Dyke:

When I was told that you had been selected to direct Tarzan, the Ape Man for M-G-M I was naturally delighted,and now that I have seen the picture, I wish to express my appreciation of the splendid job you have done.

This is a real Tarzan picture. It breathes the grim mystery of the jungle; the endless, relentless strife for survival; the virility, the cruelty, and the grandeur of Nature in the raw.

Mr. Weissmuller makes a great Tarzan. He has youth, a marvelous physique, and a magnetic personality.

Miss O'Sullivan is perfect - I am afraid that I shall never be satisfied with any other heroine for my future pictures - and Mr. Hamilton and Mr. Smith have added a lustre of superb character delineation to the production that has helped to make it the greatest Tarzan picture of them all.

And then there is little Cheetah! If she doesn't steal the show, I miss my guess. She is $2 entertainment all by herself.

Again let me thank you for the ability, the genius, and the hard work you have put into Tarzan, the Ape Man; and permit me to express the hope that you may direct my latest Tarzan novel, Tarzan, the Invincible, when it is filmed

Van Dyke was pleased with the letter, and it was reprinted in the trade papers.

The reason is obvious. It was far above the expectations anyone might have had, and the principal actors, Johnny Weissmuller and Maureen O'Sullivan, proved to be the ideal couple.

A great deal of thought went into mood, balance of tension and comedy, tenderness and brutality, and dialogue. Indeed, as was typical of MGM, many story conferences were held to iron out logistical problems, as well as to make the incredible, credible. Such things as Jane Parker's being British, rather than American, her renunciation of a vapid society existence, her implicit rejection of Holt because he desires the very things she has come to Africa to give up, the importance of a light-hearted mood at the outset to offset the drama that is to follow, all these and other details merited regular discussions by relevant studio personnel, including Ivor Novello, to whom much credit must be given for his vision of the central characters. And in one of these conferences, producer Bernie Hyman defined the approach to Tarzan that would dominate for the next several decades. “In all contact with the white people, Jane should act as interpreter and interlocutor; Tarzan’s reaction being instinctive and intuitive, rather than an intellectual reaction to dialogue...” He felt that if Tarzan were to be made articulate, it would make him common, a not unreasonable perspective given the ape man's lack of contact with his own kind during his formative years.

As MGM was known as a “producers' studio,” meaning that directors followed instructions from Irving Thalberg without question, one has to assume that Thalberg had a great deal of input, despite the fact that his name appears nowhere in the credits, a probability that is strengthened by the fact that Thalberg never wanted his name to appear in the credits, and books dealing with the subject do not dwell on his involvement. Yet, Woody Van Dyke was known as a Thalberg director, and accordingly, he would have followed his boss’s advice implicitly. And given the wunderkind’s gilt-edged instincts, such a scenario is entirely reasonable. But, this in no way detracts from Van Dyke's skill as a director. His background and past performances are satisfactory evidence that much of the credit for the film lies with him.

Clearly, the film’s beginning, as a last link to civilization is intended to contrast with the ensuing trek into the jungle. It allows one of the main protagonists, Jane Parker, to make the transition, after clearly explaining what she has left and what she hopes to find. Her femininity, coupled with her adventurous and determined spirit, not to mention her dexterity at handling firearms, provide the viewer the needed guarantee that she belongs, in somewhat the same way that Ann Darrow does for King Kong. The beginning of the film also allows for a substantial quantity of footage from the Trader Horn expedition, something that Thalberg undoubtedly had in mind, even though much of the footage had been ruined in transit.

The second element that is carefully contrived is the Mutia Escarpment, a forbidden zone, so terrifying in its mystery that local natives are put to death by tribal witch doctors merely for having looked at it. Its secrets guarded through the centuries by the hostile savages render its discovery all the more alluring, especially since its primary interest for the white man is the fabled elephants’ graveyard, that ‘strip of land so devout in its implications to jungle book fanciers that one could only assume the elephants took instruction in the church before dying’ (humourist, Jules Feiffer). This paves the way for the plot ingredient that would service so many of the Tarzan films, the dependable greed of the white man. Indeed, even when the dominant theme is something else, behind it lurks the omnipresent hope of financial gain.

The fact that Tarzan does not appear for the first 33 minutes of the film must be attributed to a desire for suspense, making the jungle lord’s initial appearance all the more receptive to an eager audience. Again, King Kong comes to mind as an apt comparison.

Even before she meets Tarzan, Jane is not really responsive to Holt’s overtures to her.

Jane.

You're very silent.

Holt. I feel very

silent. You know, Jane. I’m not a romantic sort of person

or anything like that.

But if we uh,...if we get through this all right, is

there any kind of chance

for me?

Jane. With me? I don't

know; I haven't thought about it much.

Holt. Well, will you? I

thought I hated this country. Since you’re here, I

almost love it.

Jane. Do you Harry? I'm

very glad.

Holt. Are you?

Jane. Glad you like Africa.

Holt. Oh, poof. (Jane

laughs) Now, you're laughing at me.

Jane. A little bit,

perhaps. But very tenderly.

Of course, when she finally meets Tarzan and has overcome her initial fear of him, the audience must realize that any hope Holt might have had for Jane is gone. Holt must realize it too. His solicitude when Jane disappears gradually turns to jealousy. Who is the savage now? His lack of feeling is revealed in the following scene.

Holt.

Am I interrupting anything serious?

Parker. Jane’s got

a theory you were wrong in killing that ape.

Holt. Wrong?

Parker. Well, cruel.

Holt. To whom? (Holt laughs.)

Jane. Why do you laugh. Harry?

Holt. Well, isn't that

the best thing to do?

Jane. Is it funny?

Holt. Funny?

Extremely... that you should be considering the feelings of a

man-ape. It’s a

pity I didn't put two bullets in it while I was at it and

finish the job.

Jane. I wouldn’t

talk like that. Don’t you think it’s being a little

melodramatic and absurd?

Holt. Absurd?

Jane. Extremely.

This subplot evanesces as the savage dwarfs enter the scene. Almost like the behaviour of the black Africans in Trader Horn, these little people are portrayed as bloodthirsty butchers, whose favourite entertainment is lowering captives into a pit to be mangled by a giant gorilla.

Much of western society’s view of primitive Africans is a fanciful one, often fed by novelists who had little real knowledge of the dark continent. It is doubtful that these primitive societies were any worse or better than so-called civilized ones. Still, from the purview of films like the MGM Tarzans, the untamed tribes in all six films reflected this stereotypical portrait.

One of the unknown factors in the production of the film was the acting abilities of its new star, Johnny Weissmuller. And as subsequent films have amply demonstrated, his thespian talents were never more than adequate, and his voice did not correspond to the character he portrayed. Yet, his athletic body and expressive face more than compensated for the deficiency, nor was this approach to Weissmuller’s performance lost on the critics.

One-Take Woody Van Dyke allowed his cameramen more time with the female stars, and it seems clear that he did the same for Weissmuller. It also explains his paucity of dialogue, although as Sol Lesser has pointed out, the relatively meagre dialogue had a more practical basis: the fact that much of the studio’s income for this and similar films derived from international sources.

The New York Evening Post wrote: “There is no doubt that [Weissmuller] possessed all the attributes. both physical and mental, for the complete realization of this son-of-the-jungle role. With his flowing hair, his magnificently proportioned body, his catlike walk, and his virtuosity in the water, you could hardly ask anything more in the way of perfection.”

Variety spoke of the “fine artless performance by the Olympian athlete.”

And from the Literary Digest...“A subtle touch of the animal nature in Tarzan is indicated in his frequent turning of the head, in his alertness in the presence of danger. It was something shown by Nijinsky in his impersonation of the Fawn.”

Of the technical aspects, we should note that one of the more important camera shots involved the elephant stampede. Circus pachyderms, with fake ears and tusks to simulate the African variety, were photographed from several angles including a pit shot, to recreate this exciting moment in the film. The inspiration for this came from Merian C. Cooper's and Ernest B. Shoedsack's expeditionary docudrama, Chang, made in 1927. These images would be later used as stock footage for many jungle films, not just the MGM Tarzans. The choreography for this action sequence was rehearsed for five days before the actual camera work.

The sequence involving the safari crossing a lake on rafts and being attacked by hippos was photographed at Lake Sherwood. Following the filming of this sequence, one of the hippos was reported missing. The animal had apparently preferred to remain in the water. A “get the hippo out of the lake” memo was circulated at MGM for a week until the animal decided, on its own, to return to dry land.

The final scenes following the death of Jane’s father were shot at Iverson’s Ranch in a canyon to the east of Garden of the Gods.

Tarzan, the Ape Man enjoyed an exceptional preview in February 1932, and was scheduled to open nationwide in March. The Lindbergh kidnapping, March 2, which garnered national attention, saw the opening postponed until March 25. The film opened in Canada three weeks later.

|

While the Hays Office did exist at the time Tarzan, the Ape Man was made, it did not yet wield the clout that it would under Joseph Breen two years later when Tarzan and His Mate was made. This did not prevent state agencies from exercising their own brand of censorship of Hollywood’s product. In New York, Dr. James Wingate, the director of the Motion Picture Division of the State Government, who would shortly be seconded to replace Colonel Joy in Hollywood, insisted on several excisions, such as the view of the crocodile dragging a native from a raft, and the close-up views of the natives being suspended and then lowered into the torture pit, claiming that such sights were inhuman and would “tend to incite to crime.” Similar views were held by the Pennsylvania censorship authorities. Yet other states, notably Illinois, Ohio, Virginia and Maryland passed the film without elimination. The Tarzan fever that gripped the public following the release of Tarzan, the Ape Man was demonstrated in the record-breaking attendance throughout the country. The rush was so great Saturday and Sunday that they advertised in the morning’s paper that they are forced to put on seven shows a day, starting at about 9 a.m. Such an unexpected success made it clear that MGM was not about to stop at one film. |

An original 1932 trade ad |

Reviews

The New York Times

Youngsters home from school

yesterday found the Capitol a lively place, with all sorts of thrills

in the picture "Tarzan, the Ape Man," and Johnny

Weissmuller as the hero; a so-called ape man; lions and leopards as

villains, apes for comedy relief, and elephants that aroused one's

sympathy and admiration.

It is a cleverly photographed film and, although some adults may doubt that Mr. Weissmuller kills two lions and a leopard with a knife, after a prolonged struggle, there is good enough camera trickery for lads and lassies and mayhap a few parents to believe that Johnny Weissmuller took his life in his hands when he agreed to act in this jungle feature.

Another player who has a rough time is Maureen O'Sullivan, who plays Jane Parker, the heroine of this pictorial transcription of Edgar Rice Burroughs' tale. Miss O'Sullivan is snatched from the ground and carried by Tarzan to his abode in the trees. Tarzan, being on excellent terms with apes whose lingo he appears to know, warns these beasts that the white girl is not to be killed or harmed. At least one presumes this, for, ape man or not, he falls in love with Jane and she with him. His vocabulary of English is as limited as that of a dog, and therefore it is all the more amusing when the girl, after trying to teach the jungle man to say "You" and "Me," asks him to let her see the color of his eyes. But she appreciates that Tarzan cannot understand her and so she, in spite of being a captive for the second time, coolly suggests that he knock when he enters her boudoir.

The scenes wherein Tarzan swings from tree to tree and takes a high dive into a lake are done most effectively. He makes a peculiar cry, a noise like blowing on a comb covered with paper, when he requires assistance. The elephants are usually on the qui vive and they lumber along to Tarzan and help him or his friends.

This fantastic affair is filmed with a sense of humor. W.S. Van Dyke, producer of "Trader Horn," was at the helm in the making of this tale, in which Harry Holt, Jane, James Parker, Jane's father, and others are bent on trying to find the legendary spot known as the "Elephants' burial ground," where there is supposed to be millions of dollars' worth of ivory. Whether there is or not matters little, for old Parker, played by C. Aubrey Smith, never lives to tell, and Jane elects to stay in the jungle with Tarzan, who, it might be said, is an apt pupil in learning to talk English as time goes on. It is to be construed that he who seeks the ivory will meet his end before he can get his men to dig up the tusks. Perhaps it is the curse of the elephants.

As a side issue here, there are a number of hippopotamuses who take great pride in extending their cavernous mouths. Mr. Van Dyke probably brought some of the pictures of the wild beasts back from his trip to Africa, but through crafty ideas and neat photography. Messrs. Aubrey Smith, Neil Hamilton, who appears as Harry Holt; Maureen O'Sullivan and others find themselves, or their shadows, in the midst of Africa. And besides lions, leopards and what not, there are also dwarfed blacks and real savages, some of them with amazing decorations on their physiognomies.

Mr. Weissmuller does good work as

Tarzan and Miss O'Sullivan is alert as Jane. Mr. Aubrey Smith makes

the most of his part.

Variety

A jungle and stunt picture, done in deluxe style and carrying large draw possibilities from the following of the Burroughs book series. Tricky handling of fantastic atmosphere, a fine, artless performance by the Olympic athlete that represents the absolute best that could be done with the character and the nationwide interest that attaches to the printed original looks like surefire box office.

Picture itself, aside from the book interest, will carry the release, which has multiple angles of appeal. Footage is loaded with a wealth of sensational wild animal stuff. Suspicion is unavoidable that some of it is cut-in material left over from the same producer's "Trader Horn" (done by the same director, by the way). These sequences have the stamp of verity, laying a convincing background for other matter that must have been done by technical tricks. The real thing is so obviously genuine that when they do work with a camera trick conviction is so set that the well-managed phonies never arouse suspicion.

The idyllic side of the story has been shrewdly handled and fortified by romantic settings and pictorial beauty that entirely disarm the grotesque situation of a civilized English girl falling in love with a young jungle savage, be he ever so ideal in stature and courage. Sequence of the young people splashing about a forest pool, for instance, has in it enough of visual beauty to discount any feeling of unreasonableness in the romantic situation. Be the situation however implausible, the mere poetic beauty of the backgrounds make it all charming.

Some of the stunt episodes are grossly overdone, but once more the production skill and literary treatment in other directions compensates for exaggerations. Tarzan is pictured as achieving impossible feats of strength and daring. One of them has him battling singlehanded and armed only with an inadequate knife, not only with one lion, but with a succession of a panther and two lions, and saved at the last minute from still a third big cat only by the friendly help of an elephant summoned by a call of distress in jungle language.

Some of these incidents invited a mild giggle, but startling graceful leaps among the tree tops by Weissmuller, swinging through the branches on creeper vines and bending tree boughs provide the progress of the weird tale with persuasive action. The athletic Johnny, in short, makes Tarzan believable, because he does with seeming ease and naturalness the things Tarzan would do.

The wild animal stuff is remarkably well managed. There is, for one thing, a monkey in the simian colony, of which Tarzan is a part, a medium-sized chimpanzee that is the last word in animal acting, the ultimate in animal high comedy, fleeing in terror from a pursuing lion, carrying messages for Tarzan, or making friends with the girl.

Picture has its thrills. One of them is Tarzan's swimming of a wide river, pursued by alligators, only to be saved in the nick of time by a friendly hippopotamus which swims up, takes the hero on its back and ferries him safely to shore. This trick was accomplished with utmost realism, although the inference is obvious that it was a device. What carried it over was a previous sequence showing a river full of hippopotami, probably a dozen or 15, and likely a cut-in from the genuine stuff gathered for "Trader Horn." Once the idea was planted, the subsequent trick slipped by.

Story that introduces the Tarzan character is slight, but played by the cast assembled with simple directness that makes it as acceptable as possible. An English trader (C. Aubrey Smith) and his young partner (Neil Hamilton) are about to start in search of the traditional elephants' graveyard where ivory abounds, when the elder man's daughter from England (Maureen O'Sullivan) appears at the trading post and insists upon going along. The three start on their dangerous project with a crowd of African natives. The adventures grow out of their travels, ending with their capture by a band of pygmies (where they gathered half a hundred dwarfs for the purpose is another Hollywood miracle) and escape when Tarzan once more alls upon his elephant friends for a final sequence recall, by its rush and whirl, the finish of "Chang."

Miss O'Sullivan acquits herself well in a difficult role, while the performance of Weissmuller really makes the picture. Whether the swimming champ will ever find another such outre role to play is the barrier to his career on the screen, but for this production he's a smash.